Albert Heijn uses Blockchain for orange juice, how about the human rights issues?

We woke up this morning to the good news that Albert Heijn is putting their store brand on blockchain. “That starts with the orange plantations in Brazil of LDC Juice. We are always aware of the working conditions and the certifications,” Albert Heijn writes on their website. Of course at Fairfood we always pay attention when we hear that there is a focus on working conditions.

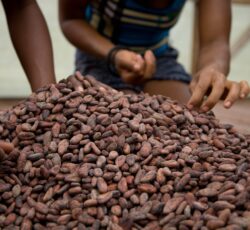

In order for oranges to become juice, they must go through a production process. In step 1 of the this process different certifications, checks and data are verified and added to blockchain. This can be seen in our infographic. In addition to the harvest period, location, name of the plantation and the Rainforest Alliance certificate, information is added to blockchain about ‘responsible and ethical working conditions.’

How?

Initial reaction: good news! After several blockchain projects of our own, we are very happy to report that blockchain is more widely known and used. Second reaction: how? How does Albert Heijn do this? What do ‘responsible and ethical working conditions’ look like when they are logged out on blockchain? More importantly, what do inadequate working conditions look like when logged out on blockchain? An essential question we focus on here at Fairfood is: how can the pickers also partake in blockchain processes?

Albert Heijn works together with LDC Juice on this project because the oranges on blockchain come from the LDC Juice plantations. This makes the project all the more interesting. LDC, together with Cutrale and Citrosuco, own the entire orange juice market. After extensive research, SOMO reports that these three multinational companies have been linked together since 2007 in relation to labor rights violations.

“The three companies are regularly accused of unfair trading practices by their suppliers (fruit growers). The companies unilaterally set prices and delivery times, and attempt to reduce purchase prices by unjustly questioning the quality of the products. In 2012, LDC exploited more than 300 suppliers this way. The affected fruit growers filed a lawsuit, which they ultimately won.”

From 2015-2017, Cutrale and Citrocusco were also fined several times for overwork, underpayment and safety issues.

In conclusion

Has LDC learned from its mistakes? Has it truly acknowledged its wrongdoings and accepted the consequences? What improvements have been made? And if Ralph van Oss, the Lead Sourcing Manager of Non-Alcoholic Drinks at Albert Heijn, tells us that the customer will soon be able to send a personal message to the pickers on the orange plantations, does this then mean that the pickers themselves will also gain access to blockchain? And not to just ‘give a like’ or acknowledge the messages from Dutch juice drinkers, but to actually confirm that they have indeed worked the agreed number of hours, and have received the correct pay for those hours. Because putting information on blockchain only adds value if all parties involved can confirm that no one has been ‘squeezed out.’

So far, we have many questions and no answers. So, we’re going to work on that and come back to you!