How new legislation can put an end to old-known trading problems

As regulation against environmental and human rights abuses in supply chains is being discussed, we take a look at some key points that must be taken into account as new rulebooks are drawn up.

While the European Commission announced that the bloc will move towards transparency, and tackle environmental and human rights abuses in supply chains, big money dedicated to making this world a better place seems to be flowing everywhere. Over 1,500 large companies now have decarbonisation plans and, according to Bloomberg, global ESG assets are on track to exceed $53 trillion by 2025, representing more than a third of the expected total of $ 140.5 trillion dollar under management. The transition to a more sustainable and fair consumption system no longer seems a distant reality, but very feasible provided the right stimulus.

Europe has been praised for showing leadership when announcing the world’s first rulebook to classify sustainable economic activity. Instead, we would rather call it accountability, as EU consumption is, for one, responsible for 16 per cent of tropical deforestation linked to international trade, according to WWF, listed only behind China. Released just yesterday, the first act of the rulebook, known as the EU Taxonomy, will be the basis of the European Green Deal, a plan to modernise and grow Europe’s economy through sustainable commercial practices, which would be established in regard to science-based criteria.

European policymakers are not alone in wanting to accelerate progress. While the continent accounts for half of global ESG assets, the U.S. registered the strongest expansion this year and may dominate the category starting in 2022. A hunt for superficial ESG claims is in motion but it has been led by investors looking to stay ahead of regulation. So far, corporate data has lacked consistency and comparability, making it difficult to access companies’ impact on key sustainability issues. Guiding the transition, investors’ new metrics and disclosures could elevate ESG reporting to the same level as financial reporting.

At Fairfood, we believe that policymakers cannot solve the problem alone, just as the private sector will not be able to clean up its supply chains overnight. Legislation can put an end to old-known trading problems. For instance, a baseline of social and environmental standards can help us redesign these dynamics through new types of incentives that could back companies focused on long-term value creation. But if we aim to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement, or simply underpin a genuine green recovery from COVID-19, here are some key points that must be taken into account as new rulebooks are drawn up.

Accountability throughout the chain

A lot of attention has been paid to the steps large investors have taken since the EU Commission approved the bill in March. There’s no doubt their immediate reaction sends a message. The success of the transition, however, still depends on how transparently companies will handle the new framework.

Commodity trader Olam recently raised the alarm about the new EU legislation aimed at preventing the import of commodities linked to deforestation and human rights abuses. Gerard Manley, chief executive of Olam’s cocoa business, told Reuters that the company fully supports the pending EU legislation. It might, however, force it to cut ties with some cocoa suppliers in its indirect supply chain, which consists of unaffiliated exporters, traders and farmers in cocoa-growing countries, such as Ivory Coast. “People will have to acknowledge they are following national and international rules. There will be verification as well. Those (that don’t comply) will not be able to supply us”, he said.

About a third of Olam’s cocoa is sourced via an indirect supply chain and two thirds via a direct chain in which the company keeps track of environmental and human rights practices. Even so, as of 2019/20, the company reported monitoring 100 per cent of its direct supply chain for deforestation, but just over half for child labour. It reflects the lack of comprehensive policies in place so far, in which companies can stop at tracking problems, instead of being held accountable for them. Although the way to tackle environmental concerns is getting clearer day-by-day, removing a child from the field remains a challenge for global companies operating in countries where such abuses are widespread. It depends on a systemic approach that usually begins with the payment of a living income to farmers. In other words, poverty alleviation measures that could ensure a child’s access to education and healthcare.

A living income, however, is a human right often denied in the agri-sector. Shifting from voluntary to mandatory regulation can finally provide an enabling environment for companies to work closely with their suppliers in order to address these gaps. In this way legislation can put an end to old-known trading problems.

The commodities ballet

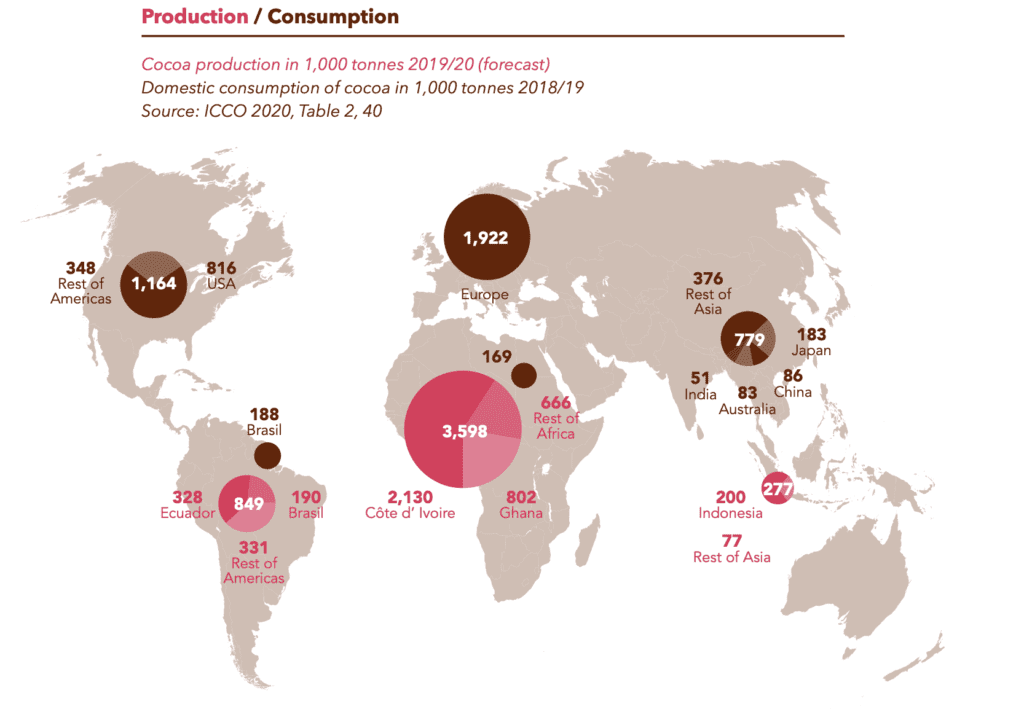

If legislation aims to truly prevent ethics abuses, it has to be carefully calibrated. Ivory Coast, for example, relies on Europe as a main customer. It exports 67 per cent of its cocoa to Europe and its cocoa sector represents 25 per cent of the economy, employing about one million small farmers. Industry experts, policymakers, and civil society representatives warn that new laws should not lead to companies cutting ties with impoverished nations that depend on commodity exports.

However, with the clock also ticking for exporting countries, new terms are coming from their side. Highly dependent on Ghanaian cocoa beans, the Swiss market is adjusting to the fact that the country no longer wants to depend on the production and export of raw materials. As part of their development goals, Ghana plans to process more cocoa and produce chocolate themselves, leaving more value in the country.

In other sectors action is already being observed. One month after the EU bill’s announcement, the Sri Lankan government baffled the edible oil industry with a ban on palm oil production and importation. The commodity often associated with deforestation was recently targeted by EU member states, such as France and Lithuania who have placed restrictions on palm oil-based biofuels. The abrupt measure simultaneously hits national producers depending on their crops, and exporters whose crops were counting on Sri Lankan market, such as Malaysia. Although the political agenda is not yet clear, the actions show the need for bottom-up inclusion. How do we make sure everyone is going in the same sustainable and fair direction?

The role of technology

Forward-looking companies have been preparing for a properly regulated system. Incorporating track and trace technologies is a great way to start. Systems based on a verified risk management capability bring down the walls between every touchpoint, creating an integrated ecosystem in which all players involved have a clear view of what is happening. If done responsibly, digitisation can give a face – and a voice! – to the people in charge of producing our food. This means redistributing data control, which could help farmers and food workers create a better understanding of the supply chain and, ultimately, even access to different markets. However, technology itself cannot drive these changes.

Looking at Eosta’s launch of the first ‘living wage avocados’, they worked closely with small farmers and the NGO IDH – The Sustainable Trade Initiative, which provided the protocol and calculation method to achieve the goal. In another act, IDH brought together big names such as Aldi Nord and Sud, L’Oréal and Unilever in their fight for living incomes. In a joint Call to Action: Better Business Through Better Wages, the group defends the need to break with old business models that look at low wages as a profitability driver.

Over the past three years, Fairfood has been helping frontrunner companies to tackle poverty in their chains through our blockchain-based traceability platform, Trace. So far, almost 3.000 farmers have been connected to the platform, and interest from the private sector in this transparency and traceability tool is growing fast.

With technology advancing, the time of making false brand promises seems to be coming to an end. Still, million-dollar companies’ operating on a voluntary due diligence basis fail to guarantee a living wage or income, which should give workers and their families access to basic needs, such as food, water, clothing, housing, education, transportation and health. It shows that tackling poverty and its many consequences, like child labour and modern slavery, will depend on new performance measures to be mainstreamed in order for big players to start their transition. To do so means going beyond sanctions, but acknowledging well-paid workers as an integral part of a profitable, sustainable and resilient business.

The Traceability Challenge

You can trace back your products in different ways, through Excel sheets or a cloud database for example. Blockchain though, is a technology that can improve traceability systems by decentralising the control of data or, in other words, democratising control along the chain.

It is a matter of time before platforms like Trace are fully incorporated in the market. To be truly democratic, it obviously depends on increasing penetration of mobile devices and IoT services in rural areas. However, ensuring that all stakeholders in the chain are in the loop depends not only on more devices or coverage, but more importantly, on clear rules on what a fair system looks like.

During the last episode of our Trace Talks series, blockchain expert Jacob Boersma discussed some of the lessons from previous Big Tech revolutions led by Google and Facebook; the unattended consequences of data collection can lead to a new sort of colonisation, in which a few companies control and profit from a large amount of data. “We really need to look at that beforehand if we want to use this for farmers and for sustainability data. How will we program ethics into technology?”, he questioned. More than simply shifting to big data or adopting tech-solutions, big companies need to be transparent about their goals, or smallholder farmers can end up trapped in new forms of exploitative systems. “The technology exists, we can use it, but we need to underpin it with the right legal parameters and the right ethics.”

Although significant, recent ESG investments still seem more like responses to pressure coming not only from consumers and policy-makers anymore, but also from investors that joined the chorus. Digitisation brings a new chance of breaking with an unsustainable and exploitative cycle while redesigning the trade system so that everyone can profit from it. Supply chains need fixing. It’s time to move beyond tracking problems by putting vulnerable parties at the centre of both legislation development and the use of technology to accelerate change.