Agroforestry’s pivotal role in future-proofing the food system

In a brand-new project with Verstegen and GIZ, we’ll be supporting Indonesian pepper farmers to transform to agroforestry. Maybe it’s our bubble, but this word ‘agroforestry’ seems to be everywhere these days. In this article, we explain that – if done right – it can bring benefits to nature, farmers and companies alike.

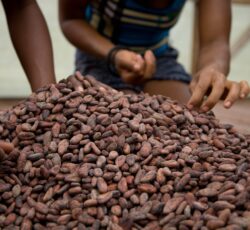

An area larger than the EU was lost to deforestation between 1990 and 2020, with EU consumption causing around 10% of losses. As a response to that, a new anti-deforestation directive adopted in Europe forbids products to enter the EU if they are associated with areas that were deforested after 2020. Another response to that, is that agroforestry initiatives are going mainstream: if farming is the reason we lost most rainforests worldwide, it’s this same sector that could save them. This message found its way from round tables and agri-food bubbles to supermarket labels now promising not only an alternative to intensive agriculture, but a regenerative one.

Yet, it is difficult to have a firm, tangible understanding of what the plantation model really delivers. Does it mean organic food? Does more tree planting make products carbon-neutral? Is it about the environment only, or do people stand to benefit?

These questions are valid, as farming models can indeed vary in the field – as can their results. The answer to all of them can be a big YES, as long as we ensure a farmer-centric approach to agroforestry. Such experiments, or “pilots” as we call them today, are ancestors to modern societies as we know them. But as warming temperatures seem to be leading the market in a regenerative direction, it’s only fair that we truly understand the real business case behind it.

Win-win: the social underexplored benefits of agroforestry

First things first. Agroforestry is a system that allows farmers to combine different types of plant species that serve different purposes, from food production, additional source of income, conservation and soil improvement by optimising available space, sunlight and water to gradually increase soil and plant health, and plant productivity. This is coming from Yayang Vionita, currently the Supply Chain Agronomist of Verstegen Spices & Sauces, with experience as the agroforestry expert at ReNature PT Cinquer Agro Nusantara (PT CAN). Today, she closely works with 30 farmers in Bangka, Indonesia, who gradually transformed their monoculture pepper plantation into pepper agroforestry plantation over the past 3 years.

Its implementation, she ensures, accommodates the needs of both nature and farmers. The first, by supporting biodiversity and conservation; while farmers aim for higher yields and stability by adding other crops to their mix while reducing risks of crop failure due to climate change and pest and disease attack – three of the core challenges faced by producers from an already warmer and drier Global South.

This win-win system results from a process that, although long, is less complicated than often advertised. “Farmers can start with a simple design and a few species, and then gradually complexify it once they have more experience and capital to scale up”, Yayang tells us. A significant benefit for farmers, however, won’t come at first, as these systems include perennial species which will produce fruits only after a few years of implementation. So, yes, long-term restoration for the soil and their farms is triggered from the start, and having various crops within an agroforestry system reduces risks if one plant fails, like in a monoculture set up. Yet, this may not be sufficient to justify the investment.

That’s where incentives come in, together with the last piece of this puzzle: companies. With a short deadline ahead of companies operating in the EU, the topic is high on priority lists. Supporting farmers during the transition of farming practices from an intensive model to agroforestry plantations can reduce risks, help sustain product supply and secure the supply chain. How, you may ask? Encouraging diversification in agricultural activity, guaranteeing a certain price, and creating a market for the commodities stemming from the agroforestry trees are ways to better connect producers to companies.

Her time with Indonesian farmers taught Yayang that even a perfect farm plan and design can be useless if farmers simply don’t want to implement or care for their agroforestry plot – what makes capacity building crucial. At the same time, greater involvement of supply chain partners in farm management allows them to control the standard and quality desired at the farm level. Hence, a farmer-centric approach to agroforestry is key if we are to encourage commitment: greater responsibility at the farm level must come with safeguarding their action. “This creates a strong farmer’s sense of belonging toward the agroforestry system”, Yayang shares.

“Implementing agroforestry cannot be the only solution for all issues in agrifood nowadays even though agroforestry plays a pivotal role in improving the farming system and environment. We also need feasible economic modeling, good strategy for post-harvest handling and product marketing, and continuous research and development to be able to address important issues in agrifood. A successful agriculture and agrifood should also be diverse not only on the environmental aspect but also social and economic aspects because these aspects are all connected and cannot be separated.”

Stable farms. Happy industry. What’s the KPI?

First, a question: should farmers transition to agroforestry systems without knowing who’s going to buy their new products? The answer is obviously no, although many pilots have tried that. Yayang explains successful agroforestry projects involve all partners from upstream to downstream. The risk to implementing the system only makes sense upon 1) guaranteed prices, 2) guaranteed sales from the buyer, 3) understanding that agroforestry is about creating shared value. Therefore, off-taker and consumer involvement in this type of project is also crucial.

As companies look for measurable impact, legislation asks for evidence of action that is not only real, but also aligned with the needs within different contexts. In other words, no one is looking for minor impact: solutions must scaleable. When it comes to regenerative agriculture, experts will work to report on KPIs on, for example, soil testing and carbon monitoring. But also on satellite and photo analysis, field studies, interviews with farmers and other various sets of proofs that are out there.

A quick google on the topic will take you to Nespresso’s website telling you about the 5.9M of native trees planted in different sourcing countries in an effort to restore coffee ecosystems and inset operational carbon footprint. “Since 2014, we have been working with AAA coffee farmers (suppliers of high-quality coffee) to reintroduce trees in and around coffee farms to strengthen the resilience of communities to climate change. A nature-based agricultural approach known as agroforestry”, the website says. Since 2014, however, a lot has changed in the debate around nature conservation, with the addition of verification of carbon emissions per plot, and more recently, with a greater integration of this type of project to a diversification of income for farmers. What, then, does 6 million trees planted actually mean in practice? And how are the non-AAA coffee farmers expected to transition to a regenerative model?

Greater enforcement proposed by the deforestation law aims to refine such claims. In a new Fairfood video, Amy Ching from Satelligence explains that with new regulations coming into force, vague claims will not sustain. That’s because there’s not only enforcement, but mechanisms for greater traceability and transparency towards due diligence processes are also changing. “Once the regulation goes into force it’s no longer sufficient to say: we are going to work towards a deforestation free supply chain in 2030. Because they need a deforestation free supply chain now”, she explains. “We can expect a transformation in the statements that are being made so that it’s no longer a far-reaching ambitious goal, but a commitment made must be implemented as they speak.”