5 questions about a fair distribution of value among food supply chains

Last week saw the 5th instalment of our Trace Talks webinar series, in which we explore a more transparent future of our food. Together with Tesco, Social Vanilla and Kumasi Drinks we asked ourselves: how can we reshape food supply chains so that everyone involved may profit? Here are the best Q&A’s from the event.

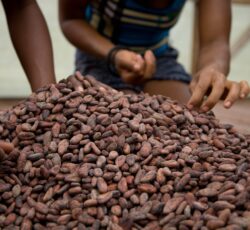

Is there a way to reshape food supply chains so that farmers – who are notoriously underpaid – get to receive their fair share? A burning question that keeps us busy here at Fairfood. In our latest webinar, we got to hear different perspectives on the matter, from start-ups to a big retailer.

Our fabulous panel consisted of Laura Kent, Responsible Sourcing Manager at Tesco, Linda Klunder, Co-founder of Kumasi Drinks, Amie N’Dong, CEO and Co-founder of Social Vanilla, and Isa Miralles, Living wage and income lead at Fairfood, under moderation of Channa Brunt, Head of Marketing and Communications at Fairfood.

While all agree on the fact that the ones at the beginning of food production chains are the ones struggling the most, due to the nature of their businesses they have taken different approaches to distributing value more evenly. They shared with us their best practices and gave insights on what they do to improve the livelihoods of farmers in their supply chains. Below you will find the most pressing questions asked during the webinar.

Missed it? Don’t worry, we got you covered! Check out the video below.

How does Fairfood’s blockchain solution Trace contribute to farmers getting their fair share?

Social Vanilla has recently started to implement Trace. Let’s have a closer look at their case: since the price of vanilla is very volatile, they decided to pay a loyalty and quality bonus to their farmers, which translates into 20-25% on top of the regular market price. By doing so, they are building up long-term, stable partnerships with their farmers, who can sustain their business.

In Denmark, Social Vanilla’s home, this story on social sustainability was enough to earn their local consumers’ confidence, but as soon as they wanted to expand to the international market, they ran into some more difficulty. Therefore, they started looking for ways to back up their story, and they found Fairfood’s solution: Trace.

Trace has the power to make it happen; making Social Vanilla’s supply chain totally transparent, and tracing their vanilla all the way down to the first link in the supply chain, the farmer. All the suppliers in the chain will be mapped digitally, and subsequently all transactions will be registered in the platform. Alongside, claims, such as paying the farmer more than the regular market price, can be verified. All this will be shown in an interface available to consumers. Thus, the next time you buy vanilla from Social Vanilla, you can scan the QR code on the package, leading to a customer interface showing the journey of the vanilla plus claims that are backed up with evidence.

This is the kind of transparency that will help raise awareness among consumers, and distinguish companies that are just telling a nice story, from the ones that are actually making a change. Plus, the traceability that Trace offers can help uncover inefficiencies in supply chains, and establish sustainable partnerships between all actors involved.

Why is 2-way traceability important?

Let’s get this straight: full traceability can only be accomplished when bidirectional traceability is viable. Meaning that one can track items in forward and backward directions. In applying this to supply chains, it will ensure that one is able to trace products from its original source to the end product and back (to ensure the evolving product is on the right track).

2-way traceability can potentially serve as an empowering method for farmers. With gained ownership of information and knowledge of the market, they will be able to participate in their supply chains more actively. Ideally, and for this the role of retailers is also essential, it could result in new business models, such as long-term contracts for a fair price or making farmers participants in the price setting mechanism.

How scalable are the solutions recommended by the smaller organisations?

Right, scalability. As much as we applaud small businesses that try to make a change, we need big corp on board to really have an impact.

Hearing from Tesco, scalability is a key issue for big retailers in creating transparent supply chains. The competitiveness on the market is humungous and prices are pushed down till the limits. To stay profitable, calculating the market price involves sticking to competition laws. This can result in barriers for them to overcome the living wage/income gap. The large advantage of big retailers, on the other hand, is the massive number of products bought, which means they have more power, potentially leading to strategic market pricing – a lower price but not at the expense of the income of the farmers.

What it all comes down to, is that we need more transparency and traceability. It all starts with knowing your supply chains and potential issues that may arise. This goes both for big and small companies. We do believe that big corp can learn from smaller organisation such as Kumasi and Social Vanilla to learn from best practices, which is why we want to keep the conversation going, like we did in this webinar.

A final, very relevant reflection was made by Kumasi, on differentiating the amount of profit that does justice to the company from “enough” profit, because only shared profits can allow fair prices.

What other challenges result from choosing transparency and traceability?

This one may take a separate webinar for us to be able to give a satisfactory answer. For one, we often hear companies fear for losing their competitive edge, for sharing information that is sensitive from a competitive point of view. Those are fears that with Trace, we solve by giving the option to make certain data anonymous. Also, with more and more legislation demanding transparency, this is an issue that will solve itself over time.

Another challenge lies in the actual data. With going transparent and traceable, you will inevitably uncover more and more data. Who owns this data? And who profits from it? This actually is a question that we did do a webinar on.

Finally, when it comes to sharing the data, it is essential to communicate the information correctly in order to avoid a backlash. In other words, you can use transparency and traceability for the base of successful storytelling, which has become a key marketing tool to gain consumers trust, but your story also needs to remain coherent and contextualised.

Let us use this occasion to reassure you that we as Fairfood, too, will remain as transparent as can be. We will therefor always share any lessons learned in blog posts, events and reports.

There seems to be a lot of attention for the topic of fair income and traceability, and yet the trend is negative, as Isa explained at the beginning of the webinar. What would be your explanation for this apparent contradiction?

We’ve noticed the awareness shift on a fair income for farmers as well, which is hopeful. The blame can be put on the lack of merger regulation, leaving room for a monopolised ground that does not allow for (rapid and easy) changes in current supply chain systems. The arrival of the covid pandemic didn’t help either and has put the global food system under even more stress.

At Fairfood, we remain optimistic on this topic, which can be reflected in our ongoing work on transparency in global food supply chains and our firm belief in human rights due diligence. As our director Sander previously said: “The pandemic is magnifying existing inequalities in food supply chains. While we are all highly dependent on smallholder farmers and workers for our food, they find themselves in exceptionally vulnerable positions. We remain optimistic, as we recognise that the world is gaining momentum to actually build up better as we collectively hit rock bottom. With greatly improved awareness for sustainability from everyone involved in global supply chains – consumers, government and private sector – we can make change happen.”