Tony’s Chocolonely, Fairtrade Original and others on a decent income for farmers

The Living Wage & Income Lab is back! Companies and NGOs from 20 countries joined in as Tony’s Chocolonely, Fairtrade Original, Eosta and Oxfam discussed ways to improve the lives of food workers and farmers. By now, we can all be sure: the topic is on the agenda and is not going anywhere!

Launched as a Change Lab for organisations working on the problem of poverty in agri-food supply chains, the Living Wage & Income Lab used to take place behind closed doors. As the pandemic normalised virtual events, we saw an opportunity to expand the conversation. To prove us right, on the morning of February 8th, 150 people from 20 countries joined in to learn from initiatives that are already making a difference in the lives of farmers and workers. We asked Tony’s Chocolonely, Eosta and Fairtrade Original: how do we accelerate change and make responsible business practices, like theirs, the new norm?

Two more sessions will take place in 2022. You can help us set the agenda for the next session through this form, and register here to be informed about upcoming dates!

The conversation was underpinned by Oxfam’s Uwe Gneiding, author of the paper Living Income: From Right to Reality. Highlighting the momentum with upcoming due diligence law on the way, he described we are at an inflection point: surrounded by growing interest but not enough commitments; many pilots versus little impact at scale; a lot of analysis but few strategies; great opportunities versus big risks. His advice to companies is to integrate a living income in their core business practices as a way to show commitment, like at procurement level. Also key: an inclusive mindset can avoid common mistakes when assessing the chain. For example, working with easy-to-access farmers rather than committing to remote rural areas where they are more vulnerable and marginalised often ends up widening the gap.

Download Uwe Gneiding’s presentation

Even though they are working in different positions, all panellists shared the clarity that a living income is not the end goal, but a first step towards correcting power imbalances in agri-food supply chains. To achieve this initial goal, more people are urgently needed to join the cause. We need governments to formulate clear rules and level the playing field, retailers to reconsider the product’s margin, and, of course, consumers, who are currently paying the most for responsibly sourced products.

As many interesting questions arose from the audience during the event, we elaborate on a few below.

Is there any proof that living incomes lead to fundamental changes in the value distribution throughout the supply chain?

Initiatives are still niche, as well as pilot results. During the session, the presenters pointed to full supply chain transparency as an enabler, as it allows to co-create with the chain partners new business arrangements and structures that can lead to more equitable outcomes across the food system, as well as to define the strategies and impact measures best suited to each context. Four main outcomes resulting from these models were covered: for farmers a living income enables a life in dignity, it triggers greater partnerships with suppliers, leading to more stability for buyers and a higher quality for the products. Moreover, when communicating their traceability efforts, transparency and accountability helps to tell a different story for their product, and avoid big surprises that could harm the companies’ credibility. After all, it takes one child working on the field for an ethical company to be questioned forever.

At Fairfood, we would add that everyone benefits from greater value reaching workers and farmers in supply chains. New arrangements, such as long-term contracts that guarantee fair prices or agreements to distribute a proportion of profits back down; as well as farmers’ participation in pricing committees, helps guarantee the longevity of agricultural activity as a whole, as poverty is the main reason why rural workers keep migrating to urban regions looking for other employment opportunities. If we continue on this road, we will be heading towards an even more concentrated market reality, with fewer and bigger actors dominating the agri-food sector, with the risk of losing old rural techniques and indigenous knowledge that are fundamental for a sustainable transition. Here we explain more.

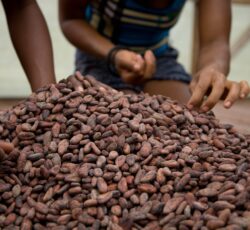

“Big commodity markets like the ones for coffee and cocoa […] actually kill the connection between the producer and the consumer. Without this connection, it’s harder to feel empathy and that’s needed to solve the issues. Shorter and less complex chains are key to foster long-term sustainable relationships.”

For countries with big buyers from regions with little to no interest in sustainability and living wage/income it is a big challenge to get everyone on board. How do you remain competitive and appealing in markets like these?

The effects of sustainability and living wage/income interventions are part of long-term partnerships and commitments; what makes it harder to engage the ones still not on board. Decent wages can result in tremendous benefits for a company such as building brand reputation, reducing long-term costs or improving productivity and quality. With mandatory due diligence close to making responsible business the norm among companies operating in Europe, we expect to see more initiatives emerging and this framework setting an example to more countries and regions still not clear on how they are covering sustainability – as in a domino effect. This, thus, is a first step to level the playing field for front-runners already transforming sustainability solutions in a competitive edge, and the laggards in the sector. You can learn more here.

How do you feel about revenue diversification for smallholder farmers in order to reduce commodity dependence, on top of paying a fair price for cash crops?

When carefully combined and according to the specific communities’ needs, different strategies and interventions can lead to increased farmers’ incomes and bargaining power. Without careful assessment, revenue diversification can simply increase farmers’ volatility to markets other than just one, as well as higher productivity can lead to more stock and falling international prices. We at Fairfood still see a fair price and greater representation in pricing decisions as fundamental to any set of measures to improve the position of farmers in global supply chains for one simple fact: it immediately translates into money in their pockets – and this is urgent. We highly recommend this read as a very elaborate answer to this question.

No shareholder in the supply chain can fix the problem of low wages and incomes alone. We need everyone involved. But consumers, for one, are mostly looking to pay the lowest price. How can we get all players involved to make living wages and incomes a reality?

Within the highly globalised market, the only contact that the consumer has with the final product is often on the supermarket shelf. Transparent supply chains enable more stakeholders, including consumers but most importantly retailers and processors, to understand the challenges faced in the first mile and take them into account when procuring or shopping. From there, risks concentrated on vulnerable farmers’ hands can be fairly incorporated and distributed within the sector – farmers, after all, should be seen as shareholders with proper representation. While legislation can lay the groundwork for fairer business practices, focusing efforts on re-establishing the connection among different actors remains an important part of the journey.