Wiard Gorter: “You can’t just throw innovations at the farmer”

We are proud to introduce the newest member of our Supervisory Board: veteran of digital innovation, Wiard Gorter. We talked to him about the enormous changes farmers are facing, the potential of digitisation and pink nails.

Imagine trying to navigate through the world of digital innovations for agri-food. Who has been helped with which innovation? How do apps integrate with each other? Are they doing that at all, or will a farmer soon be juggling twelve different applications? Where does all the data associated with digitisation disappear to? And what problems do these innovations actually solve?

Fairfood believes in the power of digitisation when it comes to redesigning the food system for good. This puts us in a field that is rapidly gaining ground, which does not exactly reduce its complexity. Then it is not just a good thing, but simply a necessity that we are assisted by a number of top-shelf experts who together form our Supervisory Board. This team keeps an eye on our work and asks critical questions when necessary. The newest name on the list is Wiard Gorter, whose extensive resume can be summarised as ‘a veteran in the field of digital innovation’. Gorter works at the interface between business and technology and often assists organisations from a board or management role in drawing up and rolling out a digital strategy. The match between Fairfood and Gorter was underlined by the stripes he earned in the field of ‘agrotech’ – technology for innovative and sustainable agriculture and horticulture.

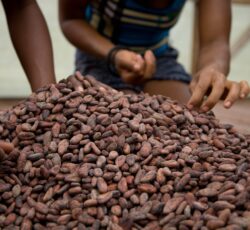

“A community that has been growing cocoa for generations is suddenly faced with unprecedented droughts. Then the knowledge they passed on from generation to generation suddenly no longer works.”

The knowledge of older generations no longer works

The agricultural sector is one of the last major sectors to follow the wave of digitisation, says Gorter. It was about time, because: “With the increasing shortages of natural resources, against a background of a fast-growing world population and consumption level, and of course the impact of climate change, the agricultural sector faces significant challenges. Small-scale farmers in particular are affected by the rapidly changing circumstances. Take, for example, a community that has been growing cocoa for generations – it suddenly experiences unprecedented droughts. The knowledge they passed on from generation to generation no longer works. The larger farmers now often have access to technology that can help with this, but a large number of small-scale farmers don’t. There is great potential for real impact there.”

But not everyone has the same impact in mind. While Fairfood uses digital innovation to empower farmers and workers, others use it to give other stakeholders (more) power. Gorter: “For example, I saw parties that offer farmers ‘free’ applications, on the condition that the farmers would continue to purchase certain products from them. Other parties may ask for insight into, for instance, the size of the harvest as ‘payment’.” A common quote in this context: “If it’s free, you’re the product.” Gorter adds: “It is important that every farmer has access to the much-needed information, and that the price she or he is paying for it is fair.”

“A farmer once showed me that he had to fill out twelve different forms with all fairly the same questions.”

What is fair? “For me, it means in the first place that the farmer’s data is not accessible to all kinds of parties in the supply chain. I find that an extraordinary phenomenon, for example, when a retailer is given access to a farmer’s administration. That directly affects the negotiating position of the farmer.” It is a discussion about the value of data, in which the word data colonisation often falls. What exactly is the value of data? More importantly: does the person who provides that data also know what the value is, and what does that person gain by doing so? This is a subject that we think about a lot at Fairfood. As a result, various partners are now working with a so-called Data Premium – a certain amount of money that farmers receive for handing over certain data. Data as a new source of income. “If farmers collect data that has value for third parties, it is only fair that they reap the benefits,” says Gorter.

Also, read our article on data colonisation and two other challenges in the digital age.

Pink nails

Trabocca is a partner with whom we have such conversations. The coffee importer is one of the users of Trace, Fairfood’s transparency platform. Menno Simons, director of Trabocca, once shared a sentiment he picked up in the field. The farmers they had asked to use Trace, he told us, were reluctant to do so, and mainly only did it because they saw it as something their customers wanted, so they had to go along with it. Never afraid to learn from our own mistakes: A case of poor communication. Ultimately, Trabocca wants to work towards a living income for which they need more insight into the price farmers to receive for their coffee – they do it for the farmer and not for themselves. But how do you show the farmer the value of such a project, in all its complexity?

Gorter responds: “You often see that participating in these types of programmes is led by pressure from the supply chain. At the time, I told my team members at UTZ: If you ask farmers to paint the left pinky nail pink, they will do so under certain pressure. That is not a sustainable starting point; farmers must be intrinsically motivated to cooperate. It is therefore important that you understand your impact well at the start of a project and make it transparent for all those involved. That is why I am enthusiastic about Fairfood; Making a real impact is the common thread running through the projects. That’s something I like to contribute to.”

“How do we ensure that the farmer at the helm – in a place where there used to be a lake and now a swirling sea with wind from all corners – arrives safely at his/her destination?”

Again, the word ‘impact’ stands out. Gorter cannot emphasise it enough. He does this with another anecdote from the field, which brings us to yet another interesting discussion: “A farmer once showed me that he had to fill out twelve different forms with all fairly the same questions for all kinds of well-intentioned projects. Twelve! In agri-tech and the sustainability sector, tools and apps are springing up like mushrooms. But ask yourself: How many apps do you really use intensively every day? Three? We need to make sure that it remains manageable for the farmer too – who is not always IT savvy.” How? “By not just throwing innovations at the farmer, but first investigating whether you really add value.” A bit of farming sobriety in the digital world.

Despite the many challenges, Gorter mostly sees the enormous potential. “We have a world of problems, but also a world of talented people and great technology. Every day there is a good new idea, and we become a little wiser. In the end, we will fix it, but we have to stay focused.” He concludes: “For now, it’s mainly about how we ensure that the farmer at the helm – in a place where there used to be a lake and now a swirling sea with wind from all corners – arrives safely at his/her destination”.