What does Corona mean for the people behind our food?

COVID-19 has become an issue of global concern that hardly goes unnoticed as cities and countries are forced into lockdowns; rules and regulations remain tight to prevent further spread. The new 1,5 metre society suffers as restaurants and other businesses remain closed until further notice, pushing the economy into a new depression. This not only has consequences for you and me. Rather, it also has worrying repercussions for the proper functioning of our food system and, consequently, the people behind our food.

In a global economy in which the products we eat in Europe are imported from places like South-America and China, the current pandemic is putting food supply chains under great pressure as they are “highly integrated and operating across borders and any disturbance in this process can disrupt the European supply chain”, state representatives of the European Liaison Committee for Agricultural and Agri-food Trade (CELCAA) and the European farmers and agri-cooperatives union, COPA-COCEGA.

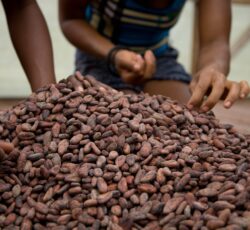

The consequences, however, stretch far beyond the European borders. According to Fairtrade Netherlands, farmers and workers suffer greatly from the results of a damaged international trading market. Under the COVID-19 pandemic farmers worldwide struggle with the exportation of goods because of a declining demand and things as banal as the lack of containers for exportation. As Fairfood, we want to know: what exactly does the epidemic mean for the people behind our food?

Economic instability

The repercussions of the pandemic are irrefutable: exporting countries, like Argentina, Uruguay and Ecuador, have reported a sudden drop in the export of farmer products, such as (soy) beans, corn, shrimps and fish. As suggested by the name, exporting countries mainly rely on the exportation of their produce as a primary source of income; if the demand keeps declining, Fairtrade Netherlands is worried for the farmers in these exporting and production countries. The organisation emphasised that if this situation keeps escalating, there will be a new economic instability that will intensify poor working conditions for farmers and workers.

Farmers themselves are also worried as they are forced to dispose from their milk, crops and expiration products since the demand has slowed down. In Ecuador, fruit export has plummeted, and prices have dropped to a new low. Farmers are forced to sell their fruit on the local market, expectedly at a lower price. “It’s affecting all of the production […] in Ecuador. You do not want your fruit to grow rotten on the tree, so you sell it for whatever price you can”, says a 72-year-old farmer that sells fruit in Ecuador.

The gravity of the situation is also omnipresent in the United States, where farmers are forced to throw away thousands of gallons of milk due to low demand. Milk production however, has not reached a standstill: the high perishability of dairy products make it impossible for farmers to halt production. As a result, farmers continue incurring costs without generating the necessary profit to maintain a healthy business.

Uncertainty

Juan Pablo Lasso Argote, a coffee farmer from Colombia, exports all his coffee produce to Europe, more specifically to the Netherlands. The farmer tells us that he expects the coffee industry to be less susceptible to the consequences of declining demand as there will always be a market for coffee, not only in Europe, but also in Colombia. However, if international demands drop and the farmer cannot ship his coffee to Europe, he will face the same problem as the fruit farmer in Ecuador: “In the case that I cannot ship my coffee to Europe, I will have to sell it on the local market, where the price is twice as low as compared to the current price that I am getting from exporting my coffee to the Netherlands.”

The biggest problem that the coffee farmer is facing right now is the uncertainty of the situation. Argote: “Since all the coffee is being exported to Europe, my main concern is that we do not know how much coffee we are going to export.” As the owner of his own farm, Argote is working with fourteen different farmers to deliver high-grade coffee to his buyers in Europe. “As the one responsible for these farmers, I have to figure out how to distribute the amount of coffee that Europe demands between the fourteen farmers, because no one can stay outside of the exportation process.” As the farmers are facing uncertainty with their primary source of income, they remain positive as they hope the demand in Europe does not lessen because of the current measures.

Social (political) instability

A characteristic of the agricultural industry is that it depends on seasonal workers who often travel to foreign countries to make a living. However, the new invisible walls that the COVID-19 measures have built around us make it complicated for seasonal workers to get within foreign walls. In the United States for instance, Mexican farm workers are being declined their H-2A visas – which enable them to work on farms across the United States. In a ‘normal’ year, some 200 thousand foreigners will travel to the US with temporary H-2A visas to work in the agriculture sector.

Evy Peña, legal advocate for migrant workers in the US says: “We tend to think about the food we’re eating and not the people growing it.” She fears that the misinformation about the coronavirus and temporary cancellation will exacerbate “fraud, illegal recruitment, unpaid reimbursement, and overcrowded living quarters.”

If anything, the pandemic is pointing out the flaws in our systems, exacerbating them. A non-food related but very painful example we see in the world of fashion, that is maintaining equally long, border-crossing and clouded supply chains. In Singapore, the fragile and tainted supply chain that has been exploited for years on end is struggling as unemployment rates skyrocket due to a fallen export market; big fashion retailers are cancelling orders which have already been completed – not paying for them. As a result, workers remain unpaid regardless of the work hours they already made. The fact that the fashion industry pertains to a global scale indicates a degree of shared responsibility to all stakeholders along the value chain. We cannot have the ‘smaller’ supply chain partners take the fall for us, when we have a shared responsibility.

As economic instability, uncertainty and social (political) instability caused by corona keep growing, there will be an inevitable downwards spiral, as each factor feeds into another. This is not only the time to ‘support our locals’, but to implement what social farmer Jan Huijgen has named as the “new social movement” – consumers and farmers need to stand together and strive for a sustainable food system. Now and post-corona.