Why income and wages are key to regaining trust in the food sector: Calling on the EU to make them a human right

Accountability starts with paying your workers a fair price. But how exactly do we get there? European recognition of the importance of living wages and incomes is critical to boost corporate action against poverty and regain trust in the food sector.

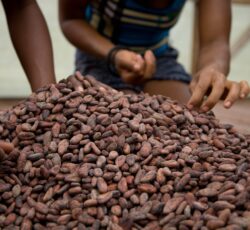

A chocolate bar you bought in a Dutch supermarket was probably made by a Swiss company, with cocoa from Ghana and sugar from Brazil. Beautiful tales of a globalised world. Except for the fact that that Swiss company, Nestlé, is a billion-dollar chocolate company, while many of its first-mile workers – the cocoa farmers – live below the poverty line. And by now, you probably know this problem isn’t exactly unique to Nestlé.

Some numbers. Dependence on agriculture for low-income countries is huge. It can amount to a third of their gross domestic product – which, together with few regulation and monitoring in place, explains why violations are easily overlooked. Today, 29% of people in modern slavery, on top of 70% of all child labourers (an absurdity that nears 100 million) are working in agriculture. Looking at bad environmental practices: 51% of the global forest loss between 2001 and 2015 came at pasture and crops’ expenses.

That’s precisely what the European Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence directive can now stop. That is, if we manage to dodge the lobby taking place against the mentioning of living wages and incomes in this directive. The move threatens to jeopardise a much-needed revision of pricing strategies, and goes against a growing consensus that before promising sustainable products to consumers, companies must make sure their suppliers are able to afford a decent life and production costs.

In a pre-pandemic world, big words on impact could often be enough to get consumers on board. But a reality of empty supermarket shelves and expensive staples have taught us all to pay more attention to our food’s origin. Today, less than half of all Europeans trust the integrity of their food.

A minimum wage is not a living wage: the letter we signed with other 60 companiesThe high price of weak due diligence

Let us explain why human rights due diligence in the food sector is critical if we are to regain the consumer’s trust. Lean supply chains have proven less valuable than they might seem: low costs turned into crippling bills as soon as the COVID-19 pandemic hit. With the invasion of Ukraine, today’s bottlenecks have reduced global GDP by at least 1%. Shareholders were hit, as were consumers. But long before inflation hurt rich countries, countries in Latin America, Southeast Asia and Africa already had smallholders and farmworkers as the ⅓ of the poorest in the world.

Without recognising living wages and incomes as a human right, the new EU directive would fail the people behind our food. Exposed to shocks triggered by extreme weather events, pests, and crop diseases, let alone a war and a pandemic that brought supply chain disruptions abruptly, farmers have more than a job to lose. As temperatures rise, the area suitable for growing coffee in Latin America, for example, is expected to reduce by up to 50% by 2050. That means a coffee crisis, as the region is home to five of the top 10 producers in the world. But it also means that 14 million families depending on the industry across the continent are threatened in their very existence.

As poverty arises, big money seems to be flying in all directions – except into farmers’ pockets. In West Africa, cocoa crops can account for 70% of the income of around 2 million smallholders. Still, they only touch 5% of the chocolate industry revenue. In coffee and banana chains, similar statistics has led to farmers’ children moving away from farming as an activity, compromising the intergenerational sustainability of production. That’s why ambitions to make the value chain resilient or sustainable must start with reviewing this norm.

In a capitalist system, it is not surprising that we are persistently avoiding talking about rising prices and wages, and instead focus on other solutions, such as diversifying farmers’ sources of income, improving efficiency, administration or land management. These are still critical to increasing farmers’ resilience, as put by Voice Network’s Antonie Fountain, but “price is still the best fertilizer.”

We don’t need to focus on good agricultural practices until there’s a business case for farmers to actually implement. That means we need proper purchasing practices and governance in place before it’s fair to ask a farmer to spend a lot of time working on what he needs to be doing. We’ve been doing this in the last 20 years: incredible investments and efforts for marginal gains at best. We need to move away from that.

Slowly, the food sector is starting to accept that its sustainability depends, thus, on keeping these communities active and thriving. Nestlé recently committed to tackling child labour, promising an additional 500 Swiss Francs to farmers yearly until 2025 as part of a 1.3 billion Swiss Francs investment to turn their cocoa sustainable by 2030. To access the money, farmers need to comply with a set of requests that includes sending their kids to school. No rationale, however, explained if the number is connected to living income benchmarks for the chosen regions.

The pledge echoes the Living Income Differentiation (LID) created by the Governments of Ghana and Côte D’Ivoire. In theory, the supplement of 400 dollars paid by companies per 1,000 kilos of cocoa establishes an income floor to protect farmers from market fluctuations. In practice, it raises red flags. How the results of extra cash, as well as extra cocoa on the market, will be assessed is still to be seen. No extra support, such as schools processing facilities, or training for farmers were announced. Some level of arbitrariness is also seen as increasing devaluation of African currencies is not converting into more subsidies for farmers, as the exchange rate is still not taken into account.

It’s not a one-man job

Without a clear directive, boxes are constantly left unchecked. Examples have shown us that isolated interventions won’t solve the problem – and higher prices alone won’t either. For some farmers, even multiplying prices by 3 would not be enough to close the income gap. What, then, is the role of prices in a successful business model for lifting farmers out of poverty?

Civil Society Organisations like the Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade have paved the way for more sustainable business practices by pointing out loopholes in legislation that allow violations to occur. Endorsed by increasingly critical consumers, they became enablers for proactive companies. We have enough to build on their models of reinforced monitoring, investments in basic community needs, and most importantly, financial rewards for products that perform better in quality or sustainability.

Times of crisis confirmed the importance of the two Fairtrade mechanisms – the Minimum Price and the Premium. Results showed they formed the crucial safety net for farmers, cooperatives, and for the continuity of their business. Comparing certified cooperatives with non-certified counterparts, food insecurity, especially among non-Fairtrade coffee and cocoa producers, is increasing given the current rising cost of living and production that affects their final available income.

The problem with the Premium is that it’s not always enough. That’s why living wage and income benchmarks are available to support companies with truly ambitious goals. Committing to closing gaps doesn’t mean you’ll get all your workers there overnight. But it makes your company’s progress tangible, as steps are measured based on a value that takes into account basic needs in different contexts.

The importance of transparency

Many international companies are still unaware of or maintain secrecy about the origin of their products or raw materials. But that shouldn’t last much longer, as concepts like mapping and traceability show us that it’s possible to keep your product’s story intact as it makes it’s way across the world. This allows you to gain clarity on the hidden costs of your products, such as difficulties and risks that often fall on the farmer.

Next to a better understanding of your chain, an optimised connection between previously distant partners is a nice side effect. All actors along the supply chain who have an ongoing business interest in the supply of agricultural products can broaden their responsibility and support workers and cooperatives. Moving beyond co-ops, first buyers and importers, we now see retailers on the other side of the chain joining the conversation. As holders of the largest share of value in the chain, they have leverage to make adjustments to purchasing practices that are key for banana growers, for example, whose prices have stagnated while costs have skyrocketed in recent decades. A Dutch national pledge from 2021 sparked a movement in Europe that today has different retailers cooperating to a living income for 75% of the chain, which in this case involves working closely with farmers’ in diversifying their crops.

Yes, diversification remains critical. And in many cases, a smarter mix of interventions can simply come from a greater connection within the chain. The use of by-products has stood out among value-added creation strategies, such as processed products made from banana peels and coffee husk infusion. A Dutch example is Kumasi Drinks, for example, which partnered with a processor in Ghana to work on creating value for farmers in the cocoa pulp, often overlooked by the chocolate industry. 30% of the extra income producers already reached participants.

Incentivising change

Innovation is welcome. But this cannot come at the expense of farmers. Pricing must reflect hidden costs if we are to deliver a value distribution that truly improves the first mile situation. Which means establishing credit schemes, funds or exploring alternative ways to support farmers in modernising their farms and adopting practices that benefit the entire chain.

Financial incentives can come in different forms, we believe. As part of a project in Indonesia, smallholders collaborating with Verstegen’s transparent narrative are benefiting from a Data Premium, for example. Just as encouragement for agroforestry has carbon credits as an ally for companies to clean up their own chains. Adding coffee farmers to the carbon market to create value in maintaining trees and fighting climate change is what we have been working on lately.

Legislation can now elevate niche lessons and trigger systemic transformation. And that’s why we reinforce: a sustainability due diligence directive is not complete without living wages and incomes acknowledged as a human right.