Paying a Living Income Reference Price: Insights from Fairtrade Original, ACPCU, and Johnny Cashew

Overcoming poverty in food supply chains means paying farmers a fair price. But how do we get to this magic number? The Living Wage & Income Lab shed light on the Living Income Reference Price (LIRP) model, exploring its application and significance for companies worldwide.

If you’re part of the Living Wage & Income Lab, you’ve probably heard a lot about strategies to create long-term partnerships and how to market living wage and income products. This time around, we went back to the beginning of it all. That moment in the project when we all wish for a faster way to get the price right. After all, is there a universal model or a quick scan available?

The subject is complex and needs to be treated as such, highlighted Aaron Petri, from Fairtrade International, when opening the session. The good news is that we have enough examples of sustainable pricing strategies to learn from. As he showed to a room made up of pricing specialists, consultants, and companies wanting to learn how the Living Income Reference Price is applied in practice. Guided by the examples of our speakers from Fairtrade Original, Johnny Cashew and ACPCU, we discussed pathways and agreed on what cannot be left out if we are to truly improve farmers livelihoods.

Main takeaways

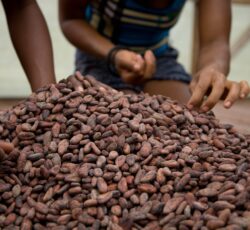

First things first: what is a LIRP and how is it calculated? Fairtrade International developed a model to quantify the price needed for an average farmer household to make a living from their crops’ sales. The approach serves to support companies seeking to go beyond the Fairtrade minimum prices. These prices were created as a safety measure to ensure that certain farmers’ costs are covered regardless of the market price – which tends to push farmers beyond international poverty lines. The LIRP is different in focus: voluntary, country or supply chain specific and calculated based on the specific components of the cost of living, as Aaron defined.

A LIRP may not be the definitive pricing solution, but it is a welcomed starting point. Fairtrade International has taken a leadership role in addressing a challenge that both the public and private sectors struggle to overcome. With two decades of experience setting minimum prices for certified products, they now propose an approach that enables farmers to progress towards a living income.

Boots on the ground

“This is a resource intensive process, but we set the stage leaner, and are getting faster in each project”, Aaron shared. A LIRP can be developed with specific partners and for specific supply chains, as was the case with Johnny Cashew in Tanzania. The research is done jointly with commodity experts. “I know the model, but I cannot be an expert in cashew from Tanzania, mangoes from Burkina Faso and all other products and origins that we have to work with”, explained Aaron. For Johnny Cashew, the journey to improve the livelihoods of 1000 cashew farmers from 4 cooperatives, depended on their team’s industry expertise and a Tanzanian-based consultant verifying the accuracy of the LIRP estimate in the cashew supply chain.

At the audience request, Cappi Wefers Bettink explained the business case of the LIRP price for cashew. In Tanzania, the Fairtrade minimum price stands at 55 US cents, while the LIRP exceeds 80 Euro cents. In practice, it has not been just about pricing; the LIRP also includes a yield target of 25 KG, and currently, only 5-10% of farmers have achieved this target. Variations exist among cooperatives due to diverse agricultural practices and disparities in access to inputs. To support farmers in reaching their potential, necessary inputs, training, and – of course – the LIRP are provided. Worth reading the full result here!

Who pays the bill?

Paying higher prices does not necessarily mean pushing the cost to the final consumer. For Johnny Cashew, support came from an actor that is often skipping our lab sessions: the retailer. LIDL committed to absorb the farm-gate price increase to a LIRP, and Cappi explained that making the sales partners familiar with the concept was key “so they also feel responsible as a company”.

For Fairtrade Original, as a coffee brand, the additional cost of paying a LIRP is shared with retailers and consumers. The company’s mission to enable farmers to achieve a living income is based on a holistic approach consisting of long-standing partnership, sustainable prices and living income interventions. And paying the LIRP is one tool in the box for achieving living income. Lena Knoerzer explained that different available LIRP studies already guide their coffee trade relationships in Colombia, Peru and Uganda – and the social enterprise is also working together with Fairtrade International on establishing a LIRP for coconut. The success, she said, lies in collaboration on this journey towards a living income.

“The farmer is an entrepreneur, and has their own business model. They know about their costs of production, productivity, and income diversification – and those are all interventions we work with our local partners.”, Lena Knoerzer shared to introduce her partner in Uganda, ACPCU. Joining virtually, Derrick Komwangi spoke on behalf of the coffee exporter producer collective that brings together 26 cooperatives and 16,135 farmers – and Fairtrade Original sources from two of these coops. “We would like to see this type of commitment reaching more farmers”, Derrick said.

On the ground, he added, it’s not just about who pays the price, but also how they can calculate the numbers, verify and show consumers and retailers. For ACPCU, reaching this transparency to show that a LIRP was paid depends on greater digitisation and proof of payments. In a joint project with Fairfood and Fairtrade Original, ACPCU found support to digitalise farmer records and keep up with the demand for more sustainable coffee.

“This is a shared responsibility. The market is going towards sustainable consumption, people want to know about the coffee they drink, and the impact on it. If this is what it takes for us, producer organisations, we are willing to do that. It is a transition, and we must all take a multifaceted approach towards that”.

Where do we go from here?

Estimating a LIRP, gathering data and finding retailers to onboard living income products are crucial tasks. But the LIRP is a piece of a complex puzzle that goes beyond defining a price or who will cover it. In a room filled with experts, valuable pathways were suggested to advance with lessons from the LIRP. Keep these notes in mind, and be sure to sign up for the newsletter to stay informed about future discussions.

- Engage retail broadly beyond private labels: commitment starts in procurement.

- Legislation in purchasing practices is needed for greater guidelines. In the lack of those, make sure to contextualise the KPIs you are using.

- Look into risks that interventions can create for farmers – even the ones aimed at positive impact: during the transition closely support farmers

- Join coalitions to lobby in the EU: all stakeholders must be engaged in calling for system change, including, guess who? The retailer.